Great Scott! Eccentric Shakespearean Thief Convicted.

- by Michael Stillman

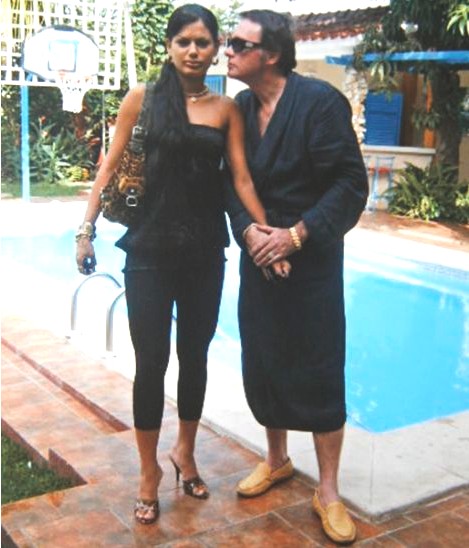

Scott and Cuban girlfriend Heidy Rios.

If the Cuban dancer was the cause of Scott's decision to sell the stolen Shakespeare, she would also become his attempted cover. Scott proclaimed that the copy had come from her family, or that of a friend. It had been in Cuba for a century or more, and since the Castros would not let her take it out of the country for authentication, he volunteered to perform the task. And that is why, he explained, he showed up at the Folger with this First Folio in hand.

Through many hearings, Scott questioned the judgment of the experts who identified this copy as being the Durham one. However, by trial time, the identification was virtually indisputable, so Scott, or his attorney, took a different tack. In this explanation, his copy was the stolen Durham, but Scott was a sucker being played by the Cubans to pawn off their stolen book. How the Cubans managed to get to a library thousands of miles away, though just a stone's throw from Scott's house, was a mystery unexplained.

Scott's trial began in June, and the prosecution's announcement that it would take three weeks was not a good omen for Scott. It takes a lot of evidence to fill three weeks. All of the expected evidence came out, along with some unexpected, and devastating information about Scott. Most notably, the prosecution revealed that Scott had been convicted a dozen times on various petty thefts, essentially shoplifting, going back to the early 1990s. He had even been convicted twice while awaiting trial on the Shakespeare charges, once for stealing a couple of books, no less, from a bookstore (they were worth about $100). Indeed, his history seems to be one of a petty thief, and not terribly good at it. The heist of the Shakespeare appears out of character for Scott, though oddly enough, he was acquitted of that charge. Technically, Scott is not a book thief. He was convicted on two other counts: handling stolen goods and removing stolen property from the country.

As to how Scott managed to live his high lifestyle on a carer's allowance and petty theft, it appears that he was good at racking up debt. He found ways to run up huge amounts of credit card and other debt. However, one can only pull this off for so long, and his attempt to maintain the playboy façade forced him into making the risky move that brought him down.

At trial, Scott's attorney attempted to paint him as "an old fool." He was simply a "mummy's boy" out of his depth, taken advantage of by a sophisticated Cuban lady. Undoubtedly he was, but not in the way his attorney tried to argue. Reportedly, Scott didn't much appreciate this line of defense, but few alternatives presented themselves. Finally, Scott pulled one last dramatic move, a head scratcher that must have left his poor attorney dazed. Late in the trial, Scott walked into the local police station and presented them with two stolen works of art and a stolen dictionary. What he hoped to achieve, other than one last splash in the newspapers, is hard to fathom. He indicated to a reporter that he was employing an element of surprise, but if he had stood up in court and proclaimed his guilt, this too would have been surprising, though hardly helpful. Perhaps Scott was already thinking beyond the verdict and hoping to reduce his sentence.

Though Scott had long had explanations for the press, when it came time to testify in court, he declined. There was nothing for him to say, or at least nothing the prosecution wouldn't tear to shreds. In America, a defendant can decline to testify at his trial, and jurors are not allowed to draw any inferences. Not so in the U.K. The prosecutor was allowed to jump on this point, asking the jury why would someone supposedly so misunderstood, fail to explain himself to the jury? Undoubtedly, the jury wondered too. His attorney was reduced to arguing that yes, Scott was a crook, but there was a possibility that he wasn't the crook in this case, so he should be acquitted. That's a weak argument and the jury wasn't buying. Conviction came swiftly, and the trial judge announced that Scott could expect a "substantial custodial sentence."

Scott's attorney had most things about his client right, except the one about his innocence. However, he missed on one other point. He described Scott as a "Walter Mitty," James Thurber's classic character who imagines he is all types of superheroes from the midst of his humdrum existence. Scott was no Walter Mitty. He didn't imagine the good life. He actually lived it for many years, despite a lack of money or notable skills at stealing. He had the fast car, fine wines, expensive clothes, international travel, and beautiful female companions. But for his dishonesty, his life would have always been that of a poor caregiver, living a lonely life in a small house with his aged mother. One can only wonder whether, as he spends his days in jail, he will regret his actions, or believe they were worth the cost.