Pulpit Preschi Prescha or the Art of Preaching

- by Thibault Ehrengardt

The art of preaching.

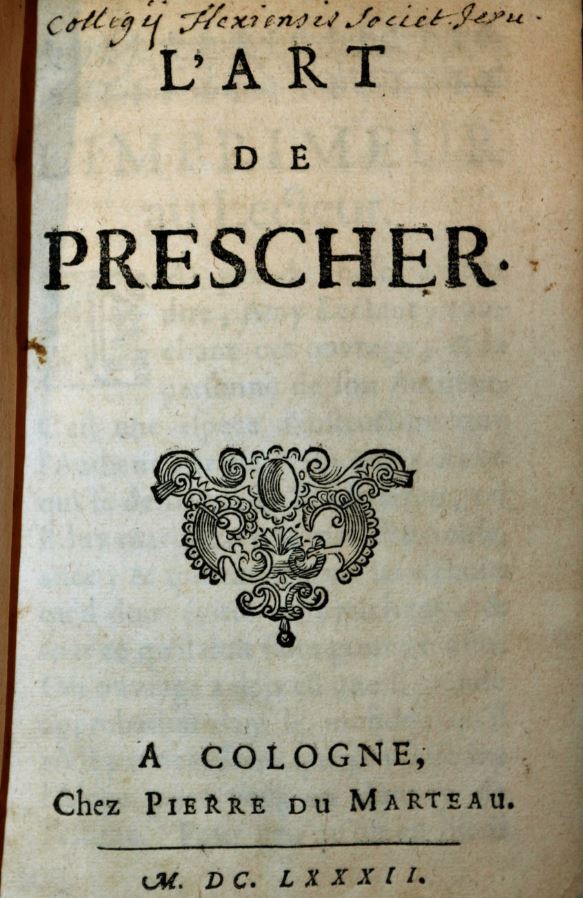

Most people enjoy reading fashionable books, I prefer weird books with unexpected subjects—some titles alone have haunted me for years like the wonderful Torrent de feu sortant de la face de Dieu—Stream of Fire Proceeding for the Face of God. The other day, curiosity urged me to buy a bizarre book entitled L’Art de Prescher—The Art of Preaching. The vast majority of religious books are plain boring to me. But this one had arguments. First, it is anonymous—a good omen, usually the signature of some satirical writer. Plus, it was printed by Pierre du Marteau, the notorious fictive printer under whose name were printed forbidden or sulphurous works. I thus expected a dark satire of the hypocritical religious. I was wrong; but I was right—to buy it. Yes my brethren, the Lord moves in a mysterious way, and He drove me to an extinct literary genre, the sermon.

Pierre de Marteau

I soon found out about my anonymous author, Pierre de Villiers (1648-1728). According to F. X. de Feller’s dictionary, he was a highly respectable man. Now, that was a first blow—Feller was a conservative man, and a Voltaire-hater; which means he would have never said any good about any anti-clerical writer. Indeed, Pierre de Villiers was first a respected Jesuit, then a respected member of the congregation of Cluny. I got scared. What if I had spent some money over a boring religious book? But then, how come Pierre de Marteau was involved? A matter of privilège—the official authorization to publish a book—, maybe? Or was it a pirate edition? Though the preface mentions previous editions that allegedly earned this work general approbation, the National Library of France lists no anterior copy—another printer’s trick, probably. Disillusioned and resigned, I nonetheless opened my book, and started to read. “We need no help to make out a good piece of work,” wrote our author. “When good, it speaks for itself—and we listen, never mistaking a bad for a good.” As a matter of fact, his pretty fine verses spoke to me—and I lent an ear.

Bourdaloue & Massillon

Writers from the Grand Siècle unveiled the torments of Man’s heart, but always elegantly—and thus nurtured a precious and tortured literature. Everything was then subject to excellence—including sermons. Two eloquent preachers became famous at the time, Fathers Bourdaloue and Massillon. “Father Bourdaloue preached divinely well in Les Tuileries,” wrote Countess de Sévigné after the religious’ first sermon in front of Louis XIV in 1670. “His talent is way beyond everything we expected.” As a matter of fact, he was called the king of preachers, and the king’s preacher. But the gentle Massillon was a serious contender who also preached before the Sun King. “Father,” said the King at the end of one of his sermons, “when I hear other preachers, I’m quite satisfied with them. But anytime I hear you, I’m hardly satisfied with myself.” According to F. X. de Feller, Bourdaloue was more of a bold conqueror (...) when Massillon was more of a clever mediator. Their sermons were printed—Bourdaloue’s works filled sixteen in-8° volumes in 1707—and now clutter up the shelves of our booksellers. The Court attended their sermons with excitement. Countess de Sévigné wrote that she visited Bourdaloue, like a country—she was quite a colourful writer—and that every single person of quality was present. But her somewhat ironic remarks tell a lot about the state of mind of the Court: “Good God!” she voluntarily swore. “Everything is below the praises Bourdaloue deserves.” The Court was a carnivorous animal, harmful to beauty and simplicity. Sermons became fashionable, and ended up far from what they were in the mouths of the Early Church Fathers. In Les Caractères, La Bruyère—who attended Bourdaloue’s sermons—underlined the change: “Nobody seriously listens to the Holy Word any more, it has become an entertainment among others; a game with emulation and gamblers.” Furthermore, many young gamblers of quality embraced a religious career as other opportunities at the time were reserved to their eldest brothers. And many were motivated by fame and vanity. “People very different from Saints nowadays climb the steps of the pulpit,” deplored the author of L’Art de Prescher. Whether saints or devils, we can hardly believe that there was a time when young people dreamt of becoming a Bourdaloue!

Ghosts & Hypocrites

In order to teach how to preach, De Villiers gave counter-examples, and drew various portraits of bad preachers à la La Bruyère. “There’s no abbot at Court whom I shall not beat,” says a proud young preacher imagined by De Villiers, “My gestures are charming, my hands are moving elegantly, I know it. / At least twenty less talented abbots have preached, whom the pulpit offered a bishopric. / All is said, on Wednesday I’ll preach for the first time.” In the pulpit like anywhere else, eloquence starts with a good text. That’s why many preachers—mostly in the country, where they dreamt of the Court—hired ghost writers. “This is quite common,” wrote De Villiers, “and thousands of orators in France, / To complacent ghost writers owe their eloquence. /Everyday people in the country, / Hear the words of some absentee.” Nevertheless, the text wasn’t all. One needed memory as well. Even the greatest forgot their lines from time to time, and when asked about his best piece of work, Massillon—though some attribute the quote to Bourdaloue—answered: “The one I remember the best.” M. De Feller had a suggestion: “We might ease their difficulties by granting the preachers the right to take a quick look at their notes from time to time.” But some young preachers didn’t even care about their blunders; their flattering friends were always here to comfort them.

Martin & the flatterers: De Villiers went to listen to one Martin: “After his trembling introduction, he hesitated, repeated himself, and got confuse’, / He drifted on a sea of uncertainty, without oars or sails to use.” At the end of the sermon, his friends praised Martin. “Humble in the middle of glory,” writes De Villiers, “he deplored his laps in memory / Though otherwise finding his sermon quite satisfactory. / “Blanks?” laughed his friends, “There was none, you must be kidding!” / Who did notice anyway? No one who was listening.” / Upon hearing his friends, Martin smiled and felt better, / Taking their words for it, he remembered he was a terrific preacher. / Standing aside,” concluded the author, “I blushed with shame to see he wasn’t doing the same.”